|

Let me start this science article with two philosophical questions:

1. Is my mind me? 2. What, really, is a human? Here’s why these questions are extremely relevant to geneticists, neuroscientists and microbiologists today:

In the last decade, we have learned a lot about the human microbiome – that is, the microorganisms that live in and on us. We’ve learned that “our” cells are outnumbered by bacteria 10 to 1. We’ve learned that our gut bacteria have the power to make us fat or skinny; to make us depressed; to calm our anxieties; and even to cause (or prevent) various digestive diseases.

If happiness can be linked to your stomach, and not just your brain, is your mind really you? If we are made up of more bacteria than human cells, what exactly is a human? These two questions have huge implications right here on earth – but, according to microbiologist Pamela Contag, they have major implications for our space programs, as well.

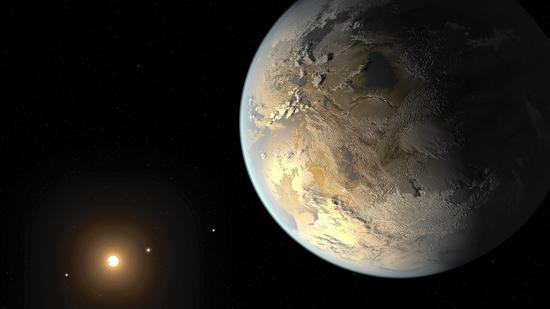

We are just beginning to understand the importance of the microbiome to human health and psychology – but we know almost nothing about how long-term spaceflight affects the microorganisms inside us.

Here’s what we do know:

The mechanism behind these changes is little understood. We know that it has to do with epigenetics, or the ways environmental factors change gene expression. But epigenetics itself is a science we are only beginning to understand. We know that the DNA in our eyes and our livers are identical, but differences in gene expression cause your eyes to be your eyes and your liver to be your liver. We know environmental factors, like emotional trauma, hunger, and social status, can turn gene expression on or off. But we don’t know much else. Moreover, while we know that (but not really how or why) microgravity affects gene expression in bacteria that live outside the body, we have no way of predicting what might happen to bacteria inside the body. Not to mention the microbes that live in the flora, dirt, air and water on the spaceship – which are necessary for processes like the carbon cycle, the nitrogen cycle and photosynthesis. I got into a 4am debate with my cab driver last night regarding the usefulness and importance of science for the sake of science. Without the space program, as Bill Nye argued on the atrocity that was The Nightly Show, we wouldn’t have cell phones, internet, or GPS.

Science for the sake of science has absolutely proven worthwhile, both in space, and here on earth. (Still don't believe me? Do a Google search about how discoveries like CRISPR and optogenetics have changed the world.) And with each new discovery, we reveal just how little we know about biology -- and why science research, even when it seems obscure, is super important.

Note: Obviously, there are several significant barriers to interstellar travel that have nothing to do with the microbiome. This is one that I found interesting, and one that most people fail to consider.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

About the Author

Eva is a content specialist with a passion for play, travel... and a little bit of girl power. Read more >

Want to support The Happy Talent? CLICK HERE!

Or Find me on Patreon!

What's Popular on The Happy Talent:

Trending in Dating and Relationships:

What's Popular in Science: Playfulness and Leisure Skills:

Popular in Psychology and Social Skills:

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed